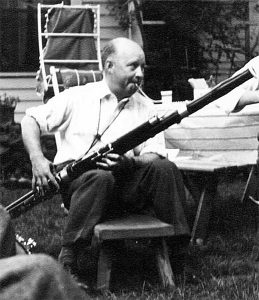

Hindemith playing his Heckel bassoon, 19401

German composer Paul Hindemith wrote more than forty sonatas. In addition to at least one sonata for each standard orchestral woodwind, brass, and string instrument, he wrote for a number of less-common solo instruments, including the English horn, the viola d’amore, and the althorn. Although he was primarily a viola player, Hindemith owned and could play many of the instruments for which he wrote; he apparently had a particular interest in the bassoon. An entry in the Heckel visitor’s log indicates that Hindemith purchased a bassoon from the firm on October 9, 1927.2

Hindemith wrote his Sonate for bassoon in 1938, during a tumultuous time in his life. Performances of his music had been banned in Germany in 1936, and in May 1938 he was one of the composers singled out for scorn at a Nazi exhibit of Entartete (Degenerate) Musik in Düsseldorf. He soon decided to leave Germany, and emigrated to Switzerland in September 1938.3. The premiere of his Sonate for bassoon took place in Zurich on November 6 of that year, performed by bassoonist Gustav Studl and pianist Walter Frey. The concert also included his Sonata for Piano, four hands, performed by Frey and Hindemith himself.4

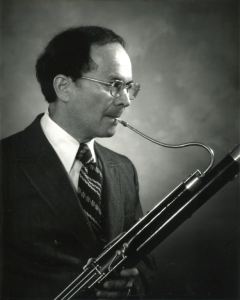

Bernard Garfield in the mid-1960s, with his black 7000-series Heckel (more info)

The earliest recordings of Hindemith’s bassoon Sonate were made in the United States, to which the composer had emigrated in early 1940. As far as I can tell, the very first recording of the piece was made by Bernard Garfield (with pianist Theodore Lettvin) on EMS Recordings, released in 1950. I contacted the Hindemith Institute in Frankfurt, and they confirmed that the Garfield recording is the earliest of which they’re aware. Leonard Sharrow also made an early recording of the piece for the Oxford Recording Company, probably some time in the 1950s, but I have been unable to find precise dates of recording or release.

Garfield, who will turn 93 this Friday, is best known for serving as the Philadelphia Orchestra’s Principal Bassoonist from 1957 to 2000. He is one of my grandteachers — Jeffrey Lyman, with whom I studied at Arizona State, studied with him, among others. Garfield has also composed a number of works, mostly featuring the bassoon in various combinations. His recordings of some of the pillars of the bassoon repertoire are still in print, and are easily obtainable, including the Mozart Concerto and Weber Andante e Rondo Ongarese (both with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra).

But, his recording of the Hindemith Sonate has never been re-released, and is quite difficult to find (this likely has to do with the fact that the owner of EMS Recordings, Jack Skurnick, died suddenly in 1952, leaving the company’s recordings to languish). I must admit that I wasn’t even aware Garfield had made a recording of the piece until San Francisco Symphony principal bassoonist Stephen Paulson made a Facebook post about three months ago, asking about its availability. It took me quite a while to track down a copy, although unfortunately it’s a somewhat worn and crackly one. But, I’m still happy to present a digitized version here:

EDIT: According to Anthony Georgeson, Garfield acquired the 7000-series Heckel in the photo above after he made this recording; he’s using a 9000-series here.

Source: http://www.hindemith.info/en/life-work/biography/1933–1939/work/the-sonatas/ ↩

Gunther Joppig, “Heckelphone 80 Years Old,” Journal of the International Double Reed Society 14 (1986), 73. ↩

Giselher Schubert, “Hindemith, Paul,” Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. Link ↩

Robert Peter Koper, “A Stylistic and Performance Analysis of the Bassoon Music of Paul Hindemith,” (Ed.D. diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1972), 115. ↩

Scott Pool

May 24th, 2017

Thanks so much for posting this! What a wonderful find!

I had no idea the premiere was in Zurich. Hindemith had written a silent film score in the 1920s about a mountain hike in the Swiss alps.

Davi Napoleon

May 9th, 2023

I am Jack Skurnick’s daughter and am delighted to see this recording available to all. (My father would have been, too.) Thank you!

David A. Wells

May 10th, 2023

Oh, how wonderful—I’m glad you stumbled across this! Also glad to know that your father would’ve been happy to see this put out into the world.