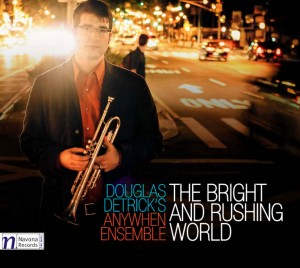

I have long intended to write more here about specific jazz recordings that include bassoon. I have many favorites spanning basically the whole history of jazz, which I’ll get to eventually. But I’ve decided to start with a recent album from a band that’s new to me. Last month I received a copy of The Bright and Rushing World by Douglas Detrick’s AnyWhen Ensemble (thanks, Dad!). This, the group’s third album, was recorded in 2012 and released in March of this year. I’ve been listening to the disc on and off over the past few weeks, and I quite enjoy it.

The ensemble describes themselves on their web site thus:

We believe in the unexpected. Our signature instrumentation sets us apart, but we make our real impact through bold new compositions that integrate chamber music conception with jazz spontaneity. We believe that great music can happen anywhere, anyhow, anywhy, and anywhen — ours is fitting music for this bright and rushing world.

Indeed it was their uncommon instrumentation that drew my attention in the first place. The group is a quintet consisting of trumpet (Douglas Detrick), saxophone (Hashem Assadullahi), cello (Shirley Hunt), bassoon (Steve Vacchi), and drums (Ryan Biesack). This very assemblage of instruments seems to bridge the chamber music and jazz worlds rather nicely. Although they all certainly appear in both realms, saxophone and drumset tend to be associated with jazz while bassoon and cello tend to be associated with classical music. Trumpet is the one instrument here that commonly appears in both musics, and it’s perhaps fitting that Detrick, the group’s leader, occupies that linchpin position. Detrick also serves as the ensemble’s chief composer. In fact, the quintet got its start playing music for his graduate composition recital at the University of Oregon, where Steve Vacchi is Professor of Bassoon and Chamber Music.

The Bright and Rushing World is a single album-length composition, divided into ten movements/tracks. They aren’t all completely continuous, but most flow into each other without substantial breaks or strong cadences. The first word that came to my mind to describe this music was “atmospheric,” but that’s not exactly right. “Spacious” might be a better descriptor. Detrick makes judicious use of silence, as well as transparent textures. The pacing is also generally gradual — themes, textures, and grooves are given plenty of time for development. There are a few hurried moments, such as pointillistic interjections in “Into the Bright and Rushing World.” But even these are relatively short, and are bookended by silence, laid back drum grooves, and/or much simpler melodic material. It is often difficult to tell exactly where the composed music ends and the improvised playing begins, which I imagine is by design.

Detrick provides the ensemble with many opportunities for exploring interesting combinations of tone colors. In the first movement (“The door is open”), saxophone, cello, and bassoon act like a single instrument, creating a lush organ-like accompaniment for Detrick’s somewhat meandering melody. In the middle of the sixth movement (“You never thought to give a name”), the four melody instruments play overlapping slithering lines, almost the sonic equivalent of a mass of writhing tentacles. Cello, bassoon, and trumpet variously emerge as solo lines from this texture, then melt back into it. It’s a very cool effect, and I can’t really do it justice with a written description. What really makes these and other timbral/textural devices within the piece work is that these players blend with each other exceptionally well. This, combined with the fact that Detrick often places the instruments (particularly the bassoon) in extremes of range, stretches the listener’s ear, sometimes making it difficult to identify exactly who is playing.

Although Detrick certainly has his own particular treatment of timbre in this piece, it is not uncommon for a bassoonist to appear in jazz groups that make interesting tone colors a feature of their music. Symphonic jazz ensembles of the late 1920s and early 1930s employed all manner of instruments in an ongoing search for new and different sounds and tone color combinations. The bandleader Paul Whiteman employed at least six wind players who doubled on bassoon, most notably Frankie Trumbauer. Later, in the cool jazz of the 1950s, arrangers favored thick textures and warm timbres. They made frequent use of instruments such as the bassoon, French horn, tuba, and cello to achieve their desired sounds. Gil Evans, the most prominent cool school arranger, used bassoons in his arrangements for Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Don Elliott, Lucy Reed, and Kenny Burrell, as well as on some of his own albums.

But while some symphonic and cool jazz groups kept their bassoonists in the background, Detrick treats all of his players as basically equal here. I’ve touched on Steve Vacchi’s ensemble playing above, but he also takes substantial solo turns in the third, sixth, and eighth movements. His solos are fluid, and he sounds at home in the mixed chamber/jazz idiom. Over the course of the album, he explores most of the bassoon’s range, from the bottom register all the way up to high E. The recording quality is excellent, and Vacchi’s rich tone comes through quite well. Here’s the third track/movement, “A seeker, insubmissive,” which has lots of prominent bassoon work — Vacchi’s solo starts at about 1:48:

If that’s not enough to convince you to go buy this album, then you can hear more samples here. The Bright and Rushing World is an interesting and valuable addition to the bassoon-in-jazz canon, and I’m looking forward to checking out the AnyWhen Ensemble’s two previous albums sometime soon: Walking Across (2008) and Rivers Music (2011).