I’m very excited today to release something to the world on which I’ve spent a great deal of time: a new performing edition of Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto in G minor for bassoon, strings, and basso continuo (RV 495), prepared using a copy of Vivaldi’s own manuscript. You can download the whole thing (for free!) at the end of this post. But first I’d like to talk a bit about my path to the piece and my methods in creating this edition. I hope that this will all prove useful to someone out there, particularly since this is one of the required pieces for the 2014 Meg Quigley Vivaldi Competition.

I’ve played a couple of Vivaldi’s other concerti in the past. But my relationship with this piece began last year, after Nadina Mackie Jackson did me the honor of asking me to write the liner notes for the first disc in what will eventually be a set of all the Vivaldi bassoon concerti. I dove into the project with my customary gusto — books littered my desk and floor, and PDFs of miscellaneous Vivaldiana delivered to me by the wizards of Interlibrary Loan similarly cluttered my laptop screen. As far as I’m concerned, research is the fun part. If I could just keep finding and absorbing more sources without ever having to actually write anything, I’d be that much happier. But aside from the various print materials, I had a more-or-less constant Vivaldi bassoon concerto soundtrack — mostly pre-release mixes of Nadina’s recording, but also versions by Michael McCraw, Sergio Azzolini, Maurice Allard, and others.

By the time I had finished the notes for Nadina, I was thoroughly fired-up about Vivaldi and his 37 bassoon concerti (plus two incomplete works). So much so, in fact, that I asked Lorna Peters, Sacramento State’s wonderful harpsichord (and piano) teacher, if she’d consider programming one of them with Camerata Capistrano, the school’s Baroque ensemble. Happily for me, she agreed, and I set about picking a piece. It’s probably not surprising that I chose one of the concerti from Nadina’s disc (RV 495), with which I’d been singing along for weeks. There are many things I love about this concerto. The first movement is fiery and flashy. The second movement foregos the upper strings entirely, creating a beautiful and passionate dialog between soloist and continuo. The third movement is just all-out intensity — it starts with the whole ensemble in driving unison (almost the Baroque equivalent of power chords), and contains what I think is one of the best licks ever written for bassoon (mm. 53–56).

I first performed the piece with Camerata Capistrano in February of this year, and luckily we’ve had many chances to present it again since then. Our tenth performance will come this Sunday, as part of the Bravo Bach Festival in Sacramento. This is the first time I’ve performed a single solo work so often, and I’ve found it to be an incredibly instructive and freeing experience. The ability to actually take chances and try new things over the course of multiple performances can shape your perception of and relationship to a piece in ways that are difficult — if not impossible — to recreate in the practice room or in a stand-alone performance. Even though I finished school a number of years ago, the one-and-done degree recital mentality is something I’m still trying to shake. But that’s a topic for another post.

As soon as I’d settled on this concerto, I knew that I wanted to create my own performing edition. At the time, I couldn’t locate an edition with string parts (I’ve since found one, available only from Germany). Plus, what better way to learn a piece backwards and forwards than to study the manuscript and make up a new score and set of parts? I could easily have used as my source the score published in 1957 as part of Ricordi’s Complete Works edition. But the editor, Gian Francesco Malipiero, provided no critical commentary and appears to have made some editorial decisions without explicitly indicating that he’d done so. So instead, I went right to Vivaldi’s own manuscript.

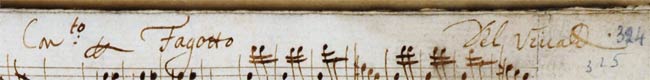

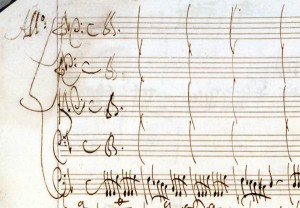

Vivaldi’s bassoon concerti (and indeed most of his works) were not published in his own lifetime, and are only known to us through a massive collection of manuscript scores that now resides at the Biblioteca Nazionale in Turin, Italy. Most of these are in the composer’s own hand, and the collection contains many incomplete sketches and drafts. These are strong indications that the collection was Vivaldi’s own compendium of his works, and as such, the scores are far from performance-ready. The composer made extensive use of shorthand techniques, including dal segni that would be awkward in performance and simply indicating unison parts instead of writing out the same music on multiple lines (see the example at right).

Beyond expanding this shorthand, I endeavored to keep my editorial hand as light as possible. But inevitably, there were a few instances in which I made changes or interpretive decisions. I have detailed these in a critical report within the score. I have not added any articulations, dynamics, ornaments, or any other performance suggestions; these are totally “clean” parts. There are, however, a few important ways in which this edition differs from the Ricordi edition (and other editions that have used Ricordi as their source):

- Throughout the concerto, Vivaldi indicates that the soloist should join the continuo line during tutti sections. Except for the few passages in which Vivaldi did not make such an indication, I have provided the soloist with the bass line in small notation. The Ricordi score leaves rests for the bassoon in all of these passages.

- Measures 211–214 of the Presto are in D minor in Vivaldi’s manuscript. In measure 211 it appears that he has written and then wiped away or scratched out a sharp symbol on an F in the Viola part, but there are no other F‑sharps marked in those measures. There is then a sudden change to D major in measure 215. The Ricordi score places the whole passage in D major.

- Measure 260 of the Presto does not exist in the Ricordi edition. This comes at the end of the last solo section, and the final ritornello is a repeat of measures 23–55. In Vivaldi’s manuscript, he wrote out a full measure of resolution (my bar 260), and then indicated a dal segno to measure 23. Ricordi omitted this measure, and instead elided the last solo cadence with the beginning of the final ritornello.

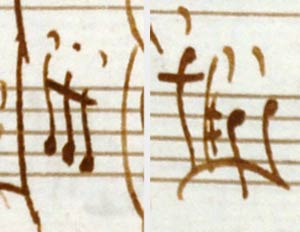

- Vivaldi wrote articulation marks over the eighth notes in the solo part in measures 249–252 and 258–259. The Ricordi edition renders all of these marks as staccati. But in Vivaldi’s hand, the marks in measures 258–259 are clearly longer than those in 249–252 (see below). Thus, I have marked the eighth notes in 249–252 as staccato and those in 258–259 with wedges.

For the actual engraving of the score and parts, I used LilyPond, which I also used for my fingering charts. It can be kind of a hassle but produces very elegant results. Also like my fingering charts, I’m releasing this under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. Basically, it means you can use, alter, copy, or distribute this however you’d like, so long as you give me credit and don’t sell it.

It is important to note that this edition does not include a keyboard reduction. It is suitable only for study or for performance with string players and a competent harpsichordist. If you need a fully written-out keyboard part, I would recommend the new bassoon/piano edition published by TrevCo Music Publishing (they list it under its Fanna number: F8#23).

And now, without further ado, here it is:

Complete Score and Parts (ZIP)

Vivaldi RV 495 — Complete Set

Individual Files (PDFs)

Vivaldi RV 495 — Bassoon

Vivaldi RV 495 — Violin 1

Vivaldi RV 495 — Violin 2

Vivaldi RV 495 — Viola

Vivaldi RV 495 — Basso Continuo

Vivaldi RV 495 — Basso Continuo (alternate version with the second movement in score)

Vivaldi RV 495 — Score

Although I’ve gone over all of this with a number of fine-tooth combs, I’d welcome any corrections, comments, or other feedback.