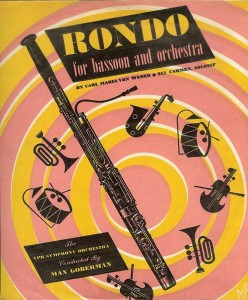

I’ve written previously about the three earliest recordings of Carl Maria von Weber’s Andante and Hungarian Rondo — two featuring German-American bassoonist William Gruner (1920 and 1926), and one with French bassoonist Fernand Oubradous (1938). As a number of people pointed out, I left out another early recording by Eli Carmen from the late 40s. I didn’t have a copy at the time, but I’ve managed to get my hands on one now. This one’s a bit of an oddball: it’s only the Rondo, it was recorded for a children’s record label, and it was released on a vinyl 78rpm disc. As far as I can tell, this recording has never been rereleased, but you can listen to it below.

Both labels of my disc — a later Children’s Record Guild release, originally recorded for Young People’s Records.

Click for a larger version.

Elias Carmen was born in New York in 1912 to Russian immigrant parents. His father was a tailor.1 He started on the French system, but switched to the German bassoon when he began studies with Simon Kovar. Carmen and Sol Schoenbach were the first two German bassoon students at Juilliard.2 Carmen played with many orchestras during his carer, most notably the Minneapolis Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, the NBC Symphony, and the New York City Ballet. He taught at both the Manhattan School of Music and Yale. Carmen died following an auto accident on December 21, 1973.3

Carmen appeared on a great number of orchestral recordings with the NBC Symphony, as well as recordings of chamber music by Beethoven, Ludwig Spohr, Arthur Berger, and Mel Powell. He also recorded Vivaldi’s Concerto in G minor, “La Notte” with flutist Julius Baker on Odyssey.4 But this partial Weber is his only truly solo recording.

Young People’s Records was established in the late 1940s, and sold records on a subscription model. Existing children’s records were meant to be played for children by their parents or teachers. But YPR wanted kids (ages 2 to 11) to actually use the records themselves. To this end, YPR was one of the first companies to exclusively use the then-new flexible vinylite for their discs, rather than the older and much more fragile shellac. A large quantity of the recorded material was written specifically for YPR — mainly songs in various styles, but also instrumental works and even mini-operas. YPR’s editorial board, which included eminent American composers and teachers Howard Hanson and Douglas Moore, no doubt encouraged the prevalence of new commissions. Recordings of Classical or Romantic composers, such as Weber, comprised a relatively small portion of YPR’s catalog.5

Records of YPR’s recording session dates evidently haven’t survived, but Eli Carmen’s Rondo was released in November 1949. Max Goberman conducted this and YPR’s other classical selections, and what’s billed here as the “YPR Symphony Orchestra” was assembled largely from Goberman’s own New York Sinfonietta. YPR emphasized music’s educational and developmental benefits in both its advertising and its packaging. The text on this record’s sleeve give a kid-friendly explanation of Rondo form:

Rondo for Bassoon and Orchestra

by Carl Maria Von Weber (pronounced Fon Vaber) 1786 — 1826When you tell an idea in words, it is called a story. When you tell an idea in music, it is called a melody. Just as you can tell a story in many different ways, so you can tell a melody in many different ways — and one of those ways is a rondo. (Other ways are marches, different kinds of dances, sonatas, sets of variations. None of these ways of telling a melody have words or stories attached to them.)

The rondo way of telling musical ideas is to keep coming back to the first idea, or melody. In this rondo — its full name is Hungarian Rondo for Bassoon and Orchestra — we hear a melody, then a new melody, then the first melody, then another new melody, then the first melody again. Sometimes these melodies are played by the bassoon alone, sometimes by the orchestra alone and sometimes by bassoon and orchestra.

And a further note “To Parents” explains why this particular work was chosen for the series:

…Young People’s Records believes the rondo to be a good form for children’s listening because it is readily apparent and acceptable. The recurrence of a basic melody is something the child can easily follow without becoming lost in intricate problems of design and form. We have chosen this particular rondo for children because of the appeal of the bassoon as an instrument.…

Hear Eli Carmen’s Rondo here:

For more about Young People’s Records and the Children’s Record Guild, see David Bonner’s 2008 book Revolutionizing Children’s Records and his web site: yprcrg.blogspot.com. The Shellackophile has also digitized and posted a number of YPR titles, which you can download (thanks to him for the image of the cover above, as it’s missing from my disc).

1920 United States Federal Census, Brooklyn Assembly District 2, Kings, New York (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, microfilm publication T625, roll T625_1146, page 6A). ↩

Sol Schoenbach, “Remembrances of Eli,” To The World’s Bassoonists 4, no. 1 (Summer 1974),

http://www.idrs.org/publications/controlled/TWBassoonist/TWB.V4.1/remembrances.html. ↩Mrs. Ivan Kempner, “Elias Carmen — Farewell,” To The World’s Bassoonists 4, no. 1 (Summer 1974),

http://www.idrs.org/publications/controlled/TWBassoonist/TWB.V4.1/carmen.html. ↩Donald MacCourt, “Elias Carmen on Recordings,” To The World’s Bassoonists 4, no. 1 (Summer 1974),

http://www.idrs.org/publications/controlled/TWBassoonist/TWB.V4.1/elias.html. ↩David Bonner, Revolutionizing Children’s Records: The Young People’s Records and Children’s Record Guild Series, 1946—1977 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2008). ↩